About Brien Foerster

Brien has explored more than 90 countries but his true passion is researching and writing about the ancient megalithic works found in Peru, Bolivia, Mexico, Easter Island, Egypt, England, and beyond. His 23 books are available on this website & amazon.com. He has appeared 15 times on the Ancient Aliens television series as well as numerous other TV and radio presentations. Brien's popular Youtube channel contains more than 850 videos related to hidden history and megalithic sites.

It is well written through accounts of the conquistadors, and Inca descendants that these people came to Cuzco as a fully developed society; teaching agriculture, metallurgy, animal husbandry, textile weaving, and the arts of warfare and politics, amongst other civilizing pursuits, to seemingly less developed people who were already inhabiting the area.

It is well written through accounts of the conquistadors, and Inca descendants that these people came to Cuzco as a fully developed society; teaching agriculture, metallurgy, animal husbandry, textile weaving, and the arts of warfare and politics, amongst other civilizing pursuits, to seemingly less developed people who were already inhabiting the area. ( or Tiahuanaco ) is clearly a mysterious place. Many writers have questioned how such an advanced culture could have survived and even thrived at its 13000 foot high elevation. Rainfall is scant here, and the only crops that grow are potatoes and quinoa, an Andean grain.

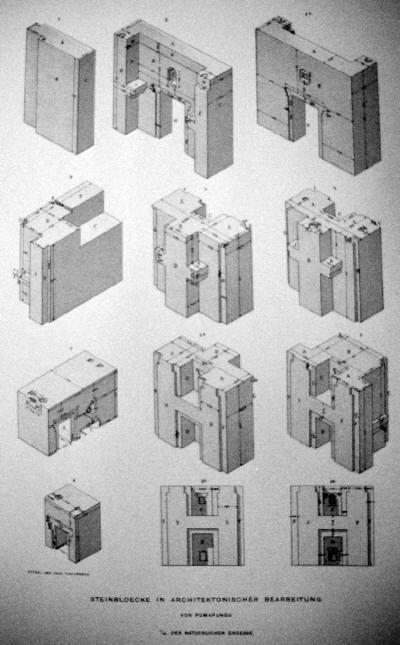

( or Tiahuanaco ) is clearly a mysterious place. Many writers have questioned how such an advanced culture could have survived and even thrived at its 13000 foot high elevation. Rainfall is scant here, and the only crops that grow are potatoes and quinoa, an Andean grain. site called Puma punku, which is very close to Tiwanaku, is perhaps the most perplexing archaeological site not only in the Andes, but all of South America. What is left of Puma punku (the gate of the Puma) is only a small percent of what must have once been there. Today we find the shattered remains, in red sandstone and diorite, of what must have once been an incredibly sophisticated technological culture. Much of Puma punku, and Tiwanaku have been removed over the centuries by local people and government officials in La Paz, Bolivia, to make other buildings, and indeed, many of the stones which made up these places were crushed to make the rail bed of the train transport system.

site called Puma punku, which is very close to Tiwanaku, is perhaps the most perplexing archaeological site not only in the Andes, but all of South America. What is left of Puma punku (the gate of the Puma) is only a small percent of what must have once been there. Today we find the shattered remains, in red sandstone and diorite, of what must have once been an incredibly sophisticated technological culture. Much of Puma punku, and Tiwanaku have been removed over the centuries by local people and government officials in La Paz, Bolivia, to make other buildings, and indeed, many of the stones which made up these places were crushed to make the rail bed of the train transport system. this have been achieved using bronze tools and obsidian tools? Highly unlikely. Indeed, the suggestion of such an idea is preposterous. Several holes, some as small as less than a centimetre in diameter, were clearly achieved with drills. And channels cut in others, some longer than a meter, must have been done with a router like tool.

this have been achieved using bronze tools and obsidian tools? Highly unlikely. Indeed, the suggestion of such an idea is preposterous. Several holes, some as small as less than a centimetre in diameter, were clearly achieved with drills. And channels cut in others, some longer than a meter, must have been done with a router like tool.

And what of the curious nodes that project out of stones, for example, inside the Coricancha, and more impressively, in the green granite polygonal blocks of the palace attributed to the Sapa Inca, Inca Roca, and perhaps best seen in the alleyway called Hatunrumiyoq, a few blocks from the Coricancha.

And what of the curious nodes that project out of stones, for example, inside the Coricancha, and more impressively, in the green granite polygonal blocks of the palace attributed to the Sapa Inca, Inca Roca, and perhaps best seen in the alleyway called Hatunrumiyoq, a few blocks from the Coricancha. Coventional scholarship states that these nodes were left, on purpose by the builders, as a projection under which a rope could be placed in order to assist in the raising of the stone to its present position. But why then would the builders, who cared so much about making the stones interlock so perfectly, so that a “human hair could not fit in the joints” leave these nodes behind? Surely they would have been chipped off and smoothed so as to not leave a trace of their presence?

Coventional scholarship states that these nodes were left, on purpose by the builders, as a projection under which a rope could be placed in order to assist in the raising of the stone to its present position. But why then would the builders, who cared so much about making the stones interlock so perfectly, so that a “human hair could not fit in the joints” leave these nodes behind? Surely they would have been chipped off and smoothed so as to not leave a trace of their presence?